Articles/ Interviews

CHALLENGING REALITY - Vegan Life Magazine

An interview with Jane Lewis on the artist's work about animal rights

CHALLENGING REALITY

Jane Lewis talks to Vegan Life about her deeply moving representational art

VL: Tell us about your own vegan journey.

JL: I gave up dairy nearly 30 years ago because of allergy rather than ethics. I had been vegetarian for many years but, while still avoiding dairy, eventually lapsed to pescatarian to occasional meat eater. Some Buddhist friends had told me about the abuse rife in the egg industry, which I ignored until I had a light-bulb moment when buying eggs in a supermarket and realized that it is impossible to supply the millions of so-called free-range eggs without the entire country being knee-deep in hens. But my real enlightenment to the horrors of animal agriculture came through social media. I saw a photograph of line upon line of calves in veal crates, and my impulse was to look away, but it gave me a feeling of nagging unease. Shortly after this I came across the Earthlings page on Facebook and wondered what the documentary film was about, so I found it on YouTube and watched it from a totally naïve perspective, unprepared for its content. Seeing that film changed my life — I became vegan overnight. That was nearly three years ago, and since then I’ve watched a lot of undercover footage of farming practices and vivisection atrocities, and have read widely about animal rights and also the health benefits to humans of a plant-based diet.

VL: How would you describe your signature style??

JL: My style is representational and realistic-looking, but not naturalistic. I want to depict ideas which at first look representational but have the disturbing aspect of being a step removed from actuality. My intention is to arrest and seduce the viewer with technique, then confront with challenging or subversive subject matter.

An idea can gestate for weeks or months or years before I get around to using it in a composition. Some ideas may never be used. I keep small sketchbooks with plans for future works, usually in the form of simple line and wash drawings, sometimes as written notes. When painting I rework an idea to the full size of the canvas (called a cartoon) before I begin the painting, and it inevitably changes and takes on a life of its own during the painting process. Most of my drawings also begin life in a sketchbook, and then evolve as I work directly on the final piece.

VL: Which materials do you work with in your pieces and why?

JL: I currently work in oil on canvas and various drawing media. I have also produced a lot of work in pastel, as pastel paintings rather than drawings. For me, oil painting has a richness and luminosity unequalled by other paint media such as acrylic, and I love its versatility and subtlety. It is capable of everything from the finest detail to chunky impasto — I, of course, go for the fine detail! It also ages with grace. In drawing I use conte crayon (a type of chalk) and charcoal, each capable of both breadth and precision, and I’m currently working in graphite pencil with coloured pencils. Because my work in oils proceeds so slowly, it is refreshing to be able to realize ideas more quickly in drawing.

I always use good quality artists’ papers, often hand-made. Since becoming vegan, I’ve begun to consider whether the materials I use are ethical. In the past synthetic brushes were distinctly inferior to those made with hair, but these days it is possible to find excellent non-hair brushes - I’ve recently bought some lovely ones from Rosemary and Co. in Yorkshire. And I am looking into what kind of glue-size is used in paper manufacture.

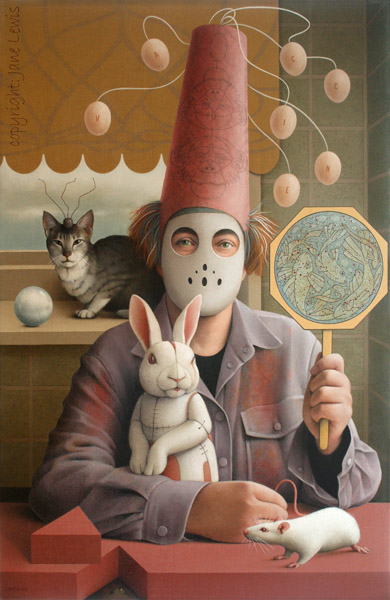

VL: We adore your ‘White Rabbit - The Vivisectionist’ image, can you tell us about the symbolism in this piece?

JL: It is based on an older composition with which I had never been satisfied, and so I decided to rework the idea. That led to it becoming a rather surreal composition because I wanted to keep certain elements and radically change others. For example there was already a human figure and a cat which I have made more sinister with the addition of the mask and electrodes on the cat’s head. The title I think speaks for itself. The painting depicts a human figure disguised by a mask, because the perpetrators of torturous experimentation on animals are frequently made anonymous by surgical masks or pixilation in video footage and photographs. In a blood-stained shirt he/she is surrounded by some of the many types of animals used in vivisection. I had in mind not a laboratory, but a less clinical interior where perhaps the vivisectionist is at home and indulging in a costumed ritual of his/her sadistic practices. So we see a cat with embedded electrodes on a windowsill with only a ball of sky for distraction. The human’s hat has a pattern of monkey faces and is festooned will floating eggs on which the word vaccine can be read — most vaccines are incubated in chickens’ eggs — and the decorative stained-glass roundel held in his/her hand depicts fish (also used in animal experiments) with spattered blood. The white rabbit of the title is at first sight a toy, but one that has been wounded and stitched, and a white rat is held in restraint by the tail. Another strange detail is the triangular piece cut from the table top to reveal the eye of a captive animal. My aim in this piece is to intrigue then challenge the viewer.

VL: Your art evokes a sense of surrealism. Which artists/artistic movements have inspired you?

JL: Yes, surrealism is an influence on my work. I first saw the work of the Surrealists at the Tate Gallery when I was 12 years old, and it had quite an impact, I‘d never seen anything like it. In later years its influence persisted as a kind of intuition in my approach to ideas. Other early influences were the work of Goya, Hogarth and the German Expressionists, all political artists in their time who produced darkly challenging pictures. Then I became entranced by the beauty of early Italian art, much of which contains an invented narrative that has an unconsciously surreal edge, as in the works of Carpaccio. My favourite contemporary artist is Paula Rego — her work is masterful and its content fascinating, and she addresses both the personal and political.

I feel that my own work has gone full circle, having begun my career with angry feminist pieces, then moving on to more lyrical personal subjects, and now producing animal rights images.

VL: ‘Earthlings 5 - Pig in Hell’ is a really strong image. What message were you focusing on when you created this piece?

JL: This is one of a series of drawings entitled Earthlings, begun last year and on which I am still working. I’ve done 14 images so far, and want to complete 20 in all. I took the title from a Viva! campaign called Pigs in Hell. I sometimes come up with a title before I’ve settled on an image. In this case, I knew I wanted to show a live pig who had already been marked up with meat cuts, because that is the reality of a pig raised from birth to become cuts of meat. This pig is on an imaginary conveyor belt with a circular saw, and a small devilish, knife wielding humanoid on wheels sits to one side, representing the hidden evil of the slaughterhouse which is itself a hell on earth. Shortly before beginning the Earthlings series I had been asked to do a painting inspired by Hieronymus Bosch for an exhibition, and the grotesque figures I invented in that piece gave me the idea of introducing something similar to both Pig in Hell and another drawing in the series By-Catch - A Marine Atrocity.

VL: Is there an animal which you feel a particular affinity to?

JL: I do like rodents. A very long time ago I had pet rats, and though I don’t want to keep captive animals now, I love rats. In the winter the occasional wild rat will come to my garden for the food I put out for birds, and there is a gorgeous squirrel, I’m convinced it’s always the same one, who feeds in the garden every winter. And so I can watch birds and rodents. I dislike the silly snobbery about grey squirrels versus red. The greys were introduced here by humans after all, and it was humans who destroyed much of the natural habitat of the red squirrel. That rodents are abused by the millions in vivisection, and that most people see them as expendable commodities for science, really upsets me.

VL: What are your hopes for the future, both as an artist and a vegan?

JL: As a vegan, and as we all say, it is forever! I can’t imagine another or a better way of life now. As an artist — after becoming vegan, at first my work and its subject matter continued as before, until I felt a profound disconnect between what I was painting and my passion for animal rights. So my imagery had to change.

For the immediate future, I’m delighted to say that my ‘White Rabbit’ painting was accepted as part of a major exhibition called New Lights which began at the Bowes Museum in November 2017 and tours to other galleries until early 2019. As a member of the Art of Compassion Project, I have contributed to a book about vegan artists, proceeds from which will be donated to Veganuary; and I am taking part in other AOC projects. I have opened an online Redbubble shop to sell cards, prints and other items featuring my work, any profit from which will be donated to animal charities, and I have already made a small donation to Viva! from this. And I’d love other vegans and vegan organizations or charities to share my images and the message they carry on social media.

Copyright: Vegan Life Magazine / Jane Lewis / January 2018

Jane Lewis talks to Vegan Life about her deeply moving representational art

VL: Tell us about your own vegan journey.

JL: I gave up dairy nearly 30 years ago because of allergy rather than ethics. I had been vegetarian for many years but, while still avoiding dairy, eventually lapsed to pescatarian to occasional meat eater. Some Buddhist friends had told me about the abuse rife in the egg industry, which I ignored until I had a light-bulb moment when buying eggs in a supermarket and realized that it is impossible to supply the millions of so-called free-range eggs without the entire country being knee-deep in hens. But my real enlightenment to the horrors of animal agriculture came through social media. I saw a photograph of line upon line of calves in veal crates, and my impulse was to look away, but it gave me a feeling of nagging unease. Shortly after this I came across the Earthlings page on Facebook and wondered what the documentary film was about, so I found it on YouTube and watched it from a totally naïve perspective, unprepared for its content. Seeing that film changed my life — I became vegan overnight. That was nearly three years ago, and since then I’ve watched a lot of undercover footage of farming practices and vivisection atrocities, and have read widely about animal rights and also the health benefits to humans of a plant-based diet.

VL: How would you describe your signature style??

JL: My style is representational and realistic-looking, but not naturalistic. I want to depict ideas which at first look representational but have the disturbing aspect of being a step removed from actuality. My intention is to arrest and seduce the viewer with technique, then confront with challenging or subversive subject matter.

An idea can gestate for weeks or months or years before I get around to using it in a composition. Some ideas may never be used. I keep small sketchbooks with plans for future works, usually in the form of simple line and wash drawings, sometimes as written notes. When painting I rework an idea to the full size of the canvas (called a cartoon) before I begin the painting, and it inevitably changes and takes on a life of its own during the painting process. Most of my drawings also begin life in a sketchbook, and then evolve as I work directly on the final piece.

VL: Which materials do you work with in your pieces and why?

JL: I currently work in oil on canvas and various drawing media. I have also produced a lot of work in pastel, as pastel paintings rather than drawings. For me, oil painting has a richness and luminosity unequalled by other paint media such as acrylic, and I love its versatility and subtlety. It is capable of everything from the finest detail to chunky impasto — I, of course, go for the fine detail! It also ages with grace. In drawing I use conte crayon (a type of chalk) and charcoal, each capable of both breadth and precision, and I’m currently working in graphite pencil with coloured pencils. Because my work in oils proceeds so slowly, it is refreshing to be able to realize ideas more quickly in drawing.

I always use good quality artists’ papers, often hand-made. Since becoming vegan, I’ve begun to consider whether the materials I use are ethical. In the past synthetic brushes were distinctly inferior to those made with hair, but these days it is possible to find excellent non-hair brushes - I’ve recently bought some lovely ones from Rosemary and Co. in Yorkshire. And I am looking into what kind of glue-size is used in paper manufacture.

VL: We adore your ‘White Rabbit - The Vivisectionist’ image, can you tell us about the symbolism in this piece?

JL: It is based on an older composition with which I had never been satisfied, and so I decided to rework the idea. That led to it becoming a rather surreal composition because I wanted to keep certain elements and radically change others. For example there was already a human figure and a cat which I have made more sinister with the addition of the mask and electrodes on the cat’s head. The title I think speaks for itself. The painting depicts a human figure disguised by a mask, because the perpetrators of torturous experimentation on animals are frequently made anonymous by surgical masks or pixilation in video footage and photographs. In a blood-stained shirt he/she is surrounded by some of the many types of animals used in vivisection. I had in mind not a laboratory, but a less clinical interior where perhaps the vivisectionist is at home and indulging in a costumed ritual of his/her sadistic practices. So we see a cat with embedded electrodes on a windowsill with only a ball of sky for distraction. The human’s hat has a pattern of monkey faces and is festooned will floating eggs on which the word vaccine can be read — most vaccines are incubated in chickens’ eggs — and the decorative stained-glass roundel held in his/her hand depicts fish (also used in animal experiments) with spattered blood. The white rabbit of the title is at first sight a toy, but one that has been wounded and stitched, and a white rat is held in restraint by the tail. Another strange detail is the triangular piece cut from the table top to reveal the eye of a captive animal. My aim in this piece is to intrigue then challenge the viewer.

VL: Your art evokes a sense of surrealism. Which artists/artistic movements have inspired you?

JL: Yes, surrealism is an influence on my work. I first saw the work of the Surrealists at the Tate Gallery when I was 12 years old, and it had quite an impact, I‘d never seen anything like it. In later years its influence persisted as a kind of intuition in my approach to ideas. Other early influences were the work of Goya, Hogarth and the German Expressionists, all political artists in their time who produced darkly challenging pictures. Then I became entranced by the beauty of early Italian art, much of which contains an invented narrative that has an unconsciously surreal edge, as in the works of Carpaccio. My favourite contemporary artist is Paula Rego — her work is masterful and its content fascinating, and she addresses both the personal and political.

I feel that my own work has gone full circle, having begun my career with angry feminist pieces, then moving on to more lyrical personal subjects, and now producing animal rights images.

VL: ‘Earthlings 5 - Pig in Hell’ is a really strong image. What message were you focusing on when you created this piece?

JL: This is one of a series of drawings entitled Earthlings, begun last year and on which I am still working. I’ve done 14 images so far, and want to complete 20 in all. I took the title from a Viva! campaign called Pigs in Hell. I sometimes come up with a title before I’ve settled on an image. In this case, I knew I wanted to show a live pig who had already been marked up with meat cuts, because that is the reality of a pig raised from birth to become cuts of meat. This pig is on an imaginary conveyor belt with a circular saw, and a small devilish, knife wielding humanoid on wheels sits to one side, representing the hidden evil of the slaughterhouse which is itself a hell on earth. Shortly before beginning the Earthlings series I had been asked to do a painting inspired by Hieronymus Bosch for an exhibition, and the grotesque figures I invented in that piece gave me the idea of introducing something similar to both Pig in Hell and another drawing in the series By-Catch - A Marine Atrocity.

VL: Is there an animal which you feel a particular affinity to?

JL: I do like rodents. A very long time ago I had pet rats, and though I don’t want to keep captive animals now, I love rats. In the winter the occasional wild rat will come to my garden for the food I put out for birds, and there is a gorgeous squirrel, I’m convinced it’s always the same one, who feeds in the garden every winter. And so I can watch birds and rodents. I dislike the silly snobbery about grey squirrels versus red. The greys were introduced here by humans after all, and it was humans who destroyed much of the natural habitat of the red squirrel. That rodents are abused by the millions in vivisection, and that most people see them as expendable commodities for science, really upsets me.

VL: What are your hopes for the future, both as an artist and a vegan?

JL: As a vegan, and as we all say, it is forever! I can’t imagine another or a better way of life now. As an artist — after becoming vegan, at first my work and its subject matter continued as before, until I felt a profound disconnect between what I was painting and my passion for animal rights. So my imagery had to change.

For the immediate future, I’m delighted to say that my ‘White Rabbit’ painting was accepted as part of a major exhibition called New Lights which began at the Bowes Museum in November 2017 and tours to other galleries until early 2019. As a member of the Art of Compassion Project, I have contributed to a book about vegan artists, proceeds from which will be donated to Veganuary; and I am taking part in other AOC projects. I have opened an online Redbubble shop to sell cards, prints and other items featuring my work, any profit from which will be donated to animal charities, and I have already made a small donation to Viva! from this. And I’d love other vegans and vegan organizations or charities to share my images and the message they carry on social media.

Copyright: Vegan Life Magazine / Jane Lewis / January 2018